Formation of caves

The word “cave” refers to a very varied range of empty spaces and hollows existing underground.

From exploration and systematic study we find that they are not distributed at random in the earth’s crust. In fact, with few exceptions, they are formed in a particular family of rocks, the limestones.

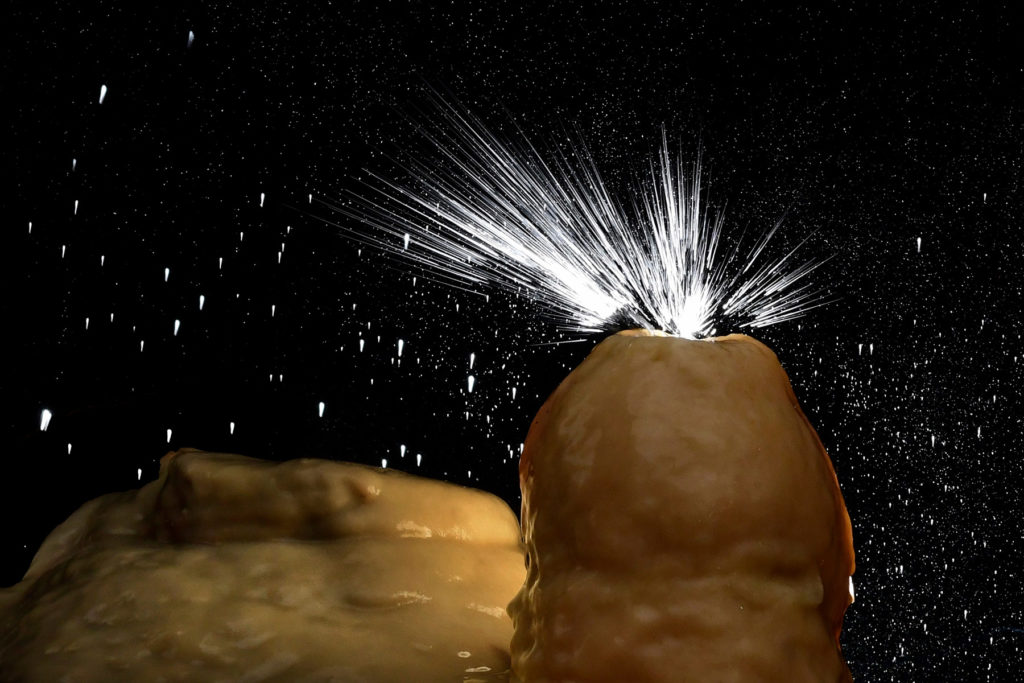

One of their basic features is that they are easily attacked and dissolved by acid solutions. This process, the surface attack of rocks by chemicals, constitutes “corrosion”. It is the method by which caves are hollowed out. Water and its circulation are the essential factors in the formation of caves. Water is indispensable to corrosion, bringing as it does the acid solutions and the dissolved substances and carrying away the debris and the residues of the chemical processes of dissolution. Finally, mechanical phenomena play a smaller part in the formation of empty underground spaces.

Once corrosion has softened the rocks, fragments may fall from the roof or walls. But in the first instance there is no change in the volume – the fallen blocks remain in the hollow. Then corrosion and water again occur to complete the hollowing out by attacking and washing away the rock fragments lying on the floor of the cave. The caves are thus the result of a chemical mechanism that dissolves and corrodes the rocks, so creating substantial empty spaces, and mechanical processes that transport the dissolved or broken products away. Although their shapes and sizes vary greatly, the empty spaces that are caves are the result of a well-defined process and, far from being scattered at random, they are in fact related according to a well-organised structure: the karst.